Equity and equality are often terms that are confused or melded together, but are they the same? Lets start with equality, the goal is to make sure everyone has access to the same things to be successful. It’s premise is to seek fairness, but in many cases this intervention can be implemented on the false assumption that people start off on a equal footing. In contrast equity attempts to understand what is needed so people can prosper. Good, is that’s it, problem solved? Unfortunately not, to expand, equity demands justice and fairness in all situations good or bad. Therefore, the onus is on treating people differently but fairly as individual circumstances dictate. In effect this is about providing the resources for the person to achieve their maximum potential.

As equality focuses on treating everyone equally, an individual is afforded the same rights and responsibilities, regardless of any personal differences. The whole tenet of equality is to prevent discrimination on the basis of; sex, race, caste, nationality, disability age and so on. This is to ensure everybody gets equal treatment in society, which is considered paramount in a democratic society, particularly in the eyes of the law. One huge problem that jumps out, while equality is simple to measure, meaning simply the same, equity is much trickier as it relates to fairness. This steers us into the choppy waters of subjectivity, as clearly not everybody agrees on what’s fair.

A debate around this often rages between left/right and the many points in between. Now we’ve defined both equity and equality and some potential issues, the problems do not stop there. Many political tribes from centrists to libertarians, talk about providing equality of opportunity, as opposed to equality of outcome. The argument often runs on the lines of; the state must treat individuals unequally in order to enforce equality of outcome and this is considered unfair in many circles.

People on the left often campaign for equal outcomes, for example the use of all-women shortlists by the Labour Party (UK) in an attempt to attain 50/50 men and women MP’s. Although, this hasn’t exactly been a success, between 1997 and 2016 out of the 170 candidates selected from all-women shortlist, just 49% have manage to reach the parliament. During this time the number of female Labour MP’s have fallen from 101 to 99. With all this in mind, I’m going to argue for a huge dose of nuance. I will propose that the optimal route depends entirely on what society is trying to achieve. Some issues should favour equity, while others would more likely benefit from equality.

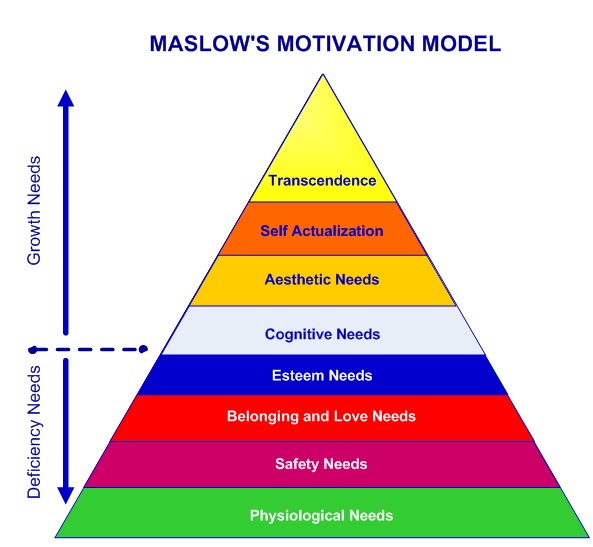

As soon as you begin an internet search on equity and equality millions of results based predominantly around gender and race are vomited onto the screen. For this piece I’m going to attempt to stay away from this region the best I can, primarily because I’ve written enough in that area recently. In this piece I want to chiefly explore socio-economic inequality and how it could be best addressed. I will use ‘Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs’ to slightly and crudely suggest that the lower we sit on pyramid regarding needs, the more we require our focus to be on equity. However, as we work our way up through the levels, utilising equality may prove to be more beneficial. For those of you who are not familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy, check out the diagram below.

For this exploration, I have decided to use the more updated 8 stage format. Initially this was a 5 stage theory, the new illustration was adopted in 1970. Maslow’s original intentions was for this to be a form of motivational theory, but I’m primarily going to utilise this as a depiction of how these needs are organised and where other factors such as personal responsibility may fit in.

Firstly, you will have most likely recognised that the pyramid is split between 4 ‘deficiency needs’ (D-needs) and 4 ‘growth needs’ (G-needs). D-needs arise primarily through deprivation, according to Maslow this motivates the person to fulfill these needs if they are unmet. For example the longer someone goes without food, the hungrier they will become. Note that to progress up the pyramid, one must in general meet the requirements of one level before moving to the next.

Towards the upper reaches of the pyramid are G-needs, in comparison these are not a deficit of anything as such, but more a desire to grow as a human being. As explained with the D-needs, an individual must work their way through the levels, eventually reaching the top level of transcendence. Progression through the ranks is rather like a game of “snakes and ladders”, moving up during the good times, but slipping back during difficult experiences such as; a loss of job or a divorce. It is also worth pointing out that most behaviour is multi-motivated, meaning an individual can be simultaneously motivated by more than one basic need.

If we observe these needs in relation to a capitalist system in which we live in, some people will struggle to gain access to the very basic needs (thus, dwelling in what I call Maslow’s cellar), while others will inhabit the ‘penthouse of transcendence’. Following the advent of neoliberalism in the late 70’s (UK) and the early 80’s (NZ, US, Aus and Can) many entities that were once considered universal are now in the hands of private corporations and are often more expensive, such as healthcare in the US. Furthermore, some people will have the resources, connections, luck and perseverance to move up through the levels, while others may have varying struggles that make life more difficult to acquire even the most rudimentary of needs.

It makes moral and economic sense to ensure that everybody has their basic physiological needs met, whether this is via their own volition, through assistance in some way or a combination of the two. These physiological needs would include; food, water, shelter and warmth. Looking at this in terms of the equity/equality conundrum, some people for a myriad of reasons often require more help than others.

Maslow proposed that the first tier contains the most important set of needs and are essential for the human body to function at an optimal level. I look at it as the foundations of human flourishing. If we have empathy for our fellow human beings, if we want to create conditions so people can thrive, therefore, contribute to society, equity at this level should be a simple decision. Vital requirements such as; food, water and shelter should be provided to those in need, not to everybody. This can be justified by stating that not everyone in society are dealt the same hand and many people do not need this level of support.

Moving one rung up we encounter ‘safety needs‘, described as; protection from the elements, security, the provision of healthcare, stability, freedom from fear and a functioning legal system. Even at this second stage, we start to approach what could be considered grey areas for some people, who would offer that some of these factors are chiefly the responsibility of the individual.

It seems perfectly logical that each human being is seen equally under the eyes of the law, which is of course is equality. Furthermore, all people should have access to adequate legal representation when required, such as legal aid. This is an obvious example of equity. By providing what is needed an individual can adequately partake in society. Here we have an example of equity in an effort to promote equality.

Another area is healthcare, in the US in particular the quality of healthcare is based on your insurance plan. In other words your social status, employment situation or your bank balance decides upon the level of care you receive. Surely, in a humane society suitable health provision is a basic human right and the best healthcare available should be afforded to all human beings.

This for me is non-negotiable, it is difficult for a society to claim civility while employing a multi tier health system. This highlights a glaring problem with capitalism, if “all people are considered equal”, as is claimed in most western societies, then care shouldn’t be based on economic status, otherwise we are contradicting the initial statement. In that case, the original statement should, therefore, be amended to read, “all social status is proportional to the wealth of the individual”.

If we take the stairs to the next floor we arrive at the level of ‘belonging and love’ needs. This refers to emotional needs such as family, friends and intimacy. It is proposed that the need for interpersonal relationships motivates our behaviour. This is where we learn about trust, intimacy, love and being part of a group. These needs are particularly strong in childhood, as we require a stable platform to flourish as an adult. Emotional and psychological needs in childhood are often protected by law to enforce a certain level of acceptable care, broadly speaking we could call this equality. However, kids are unique and have differing requirements for them to develop, which could easily be argued as an example of equity.

The 4th floor is the last of the deficiency needs and where ‘esteem’ hangs out. Maslow classified these needs into two categories.

- Esteem for oneself, such as dignity, mastery, achievement and independence

- The desire for reputation or respect from others, such as status and prestige.

When exploring what equitable processes could be put in place to facilitate these needs, much of it points to education. Creating a system that fosters critical thinking, that recognises individual talents and abilities, that delivers outstanding education, will help children to meet the deficiency needs as laid out above. Having a good start in life, with excellent education for all is one of the best ways to achieve equality or simply a fair shot at life. In this case, equity is undoubtedly the tool required to achieve this, such as putting more resources into struggling schools. This is especially poignant when considering that only 7% of the UK attend fee paying schools and yet 39% of those in position of power are privately educated. This is an example of entrenched elitism and something to be challenged.

As we leave deficiency needs (D-needs) and enter the territory of growth needs (G-needs) it becomes increasingly more difficult to find examples of when equity is valid, while providing ample justification for any actions. Many growth needs that people fight for are less of an economic or basic necessity or even a need as such, but could be more easily categorised as a want. These ‘needs’ are often found in the realm of identity politics and are much more politically driven, even though the actual requirements are less pressing. However, because these matters are pushed by often the educated, middle classes and not the powerless in our society, their demands regularly garner more attention. One of the blunt tools to gain equity is “positive discrimination” or to use the more cuddly term “affirmative action”.

This is the domain where educated, relatively comfortable, middle class, so called progressives demand a 50:50 ratio in every occupation. Correction, equal representation in only the top professions including MP’s, CEO’s and worthwhile careers, such as within the upper echelons of education. Unsurprisingly, there seems little clamour to protest for equality in order to work on oil rigs, the front line of the military and many shitty, dangerous jobs men fill on a daily basis. We are led to believe that this discrepancy is simply due to discrimination, rather than average sex differences in career preferences and life goals. There is also very little coverage about the many professions women dominate. Here are some examples:

- Medical and health service mangers

- Psychologists

- Teachers

- Medical scientists

- Financial specialists

- Accountants/auditors

- Veterinarians

- HR managers

It’s also worth acknowledging that in universities approximately 60% of students who achieve degrees are women. Women can obtain female only scholarships into STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) in an effort to address the supposed discrimination within this field. Shockingly, at the University of Oxford, an extra 15 minutes was added to computer science and maths exams, as it was thought that time pressure may adversely affect female candidates. This for me highlights when positive discrimination and the quest for equity goes too far. This is effectively social engineering, surely we would live in a freer society if people were allowed to make their own decisions regarding their lives, rather than being cajoled into a profession purely to satisfy some political narrative.

Much of this positive discrimination crosses the line, shifting from needs; food, shelter, education and health, to wants; a better job, status, prestige and more money. How in any way does this type of campaign, supported by relatively privileged people, positively affect the majority of working class, poor and the homeless? These are campaigns designed by the middle class, for the middle class and are no more than self serving ventures. Often these comparatively trivial concerns are heavily supported by politicians and the mainstream media in an effort to secure middle class votes, at the expense of the hapless working class.

I am all for using equity as a tool to combat an incongruence of human rights. Nobody should go without adequate food, shelter, heat, education, health care, protection by the law and even a means of earning money, or we must consider that we have failed as a first world society. Although, I would suggest that decisions regarding when to employ equity should be made based on tangible individual need and not simply given to particular identity groups. Equally we should not be duped into providing a further leg up for the bourgeois, educated, manipulative, middle classes who convince us that their requirements are of far greater importance than anybody else’s.

So where does personal responsibility fit in, you may ask. Many on the right suggest personal responsibility encompasses practically every choice we make. I would argue that the choices available are greatly reduced if your basic needs, primarily the bottom four blocks of Maslow’s hierarchy, are not met. In contrast, an individual like Bill Gates for example attended school where he could gain programming experience, at a time when less than 0.01% of his generation had access to computers. Further to this, he also had a mother with social connections to the chairman of IBM. These types of advantages experienced by the rich obviously provide a greater range of choices than the average person. Examples such as Bill Gates only serves to question the validity of the “personal responsibility” hypothesis within this context.

It is relatively well documented that rich kids will likely go on to be a rich adult. It fact, a child’s basic earnings can be based off a percentile of their parents income. Additionally, people who are affluent are more likely to marry, further to this, kids who have a stable two parent family tend to enjoy more fruitful lives. This information adds weight to the argument that if we decrease economic inequality, society as a whole will benefit.

Equity and equality both have their place, but if we want to provide everyone with an opportunity to thrive, equity is necessary to ensure that all people have their basic needs met, contributing to good foundations for life. Less economic inequality can increase trust and societal participation, decrease health problems, reduce crime, increase social mobility, improve education levels and even stabilise the economy. So, the question is, why wouldn’t we do what we can to raise all boats, starting with the very people who have run aground?